Photo Credit: freepik.com/storyset

In our previous (which was also the first) article of the series, we talked about survey bias and one of its types, Sampling Bias.

For those of you who are joining us for the first time and want to learn from the beginning, here’s a quick refresher about survey bias:

Survey bias refers to any act, intentional or otherwise, that influences the results of the survey unfairly towards or against a certain objective, thing, or person. It’s basically any deviation from the truth. Any act or decision that takes the survey results away from what’s really happening is called survey bias.

Important Disclaimer:

It’s almost inconceivable to create a survey questionnaire that’s free from all kinds of biases. Too many external factors play a role in survey administration, and many of those factors can be out of your control. The goal, therefore, is not to eliminate bias but to minimize it as much as possible.

By understanding what causes bias and ways to minimize it, we can create surveys that deliver the most accurate results and keep the insights as close to reality as possible.

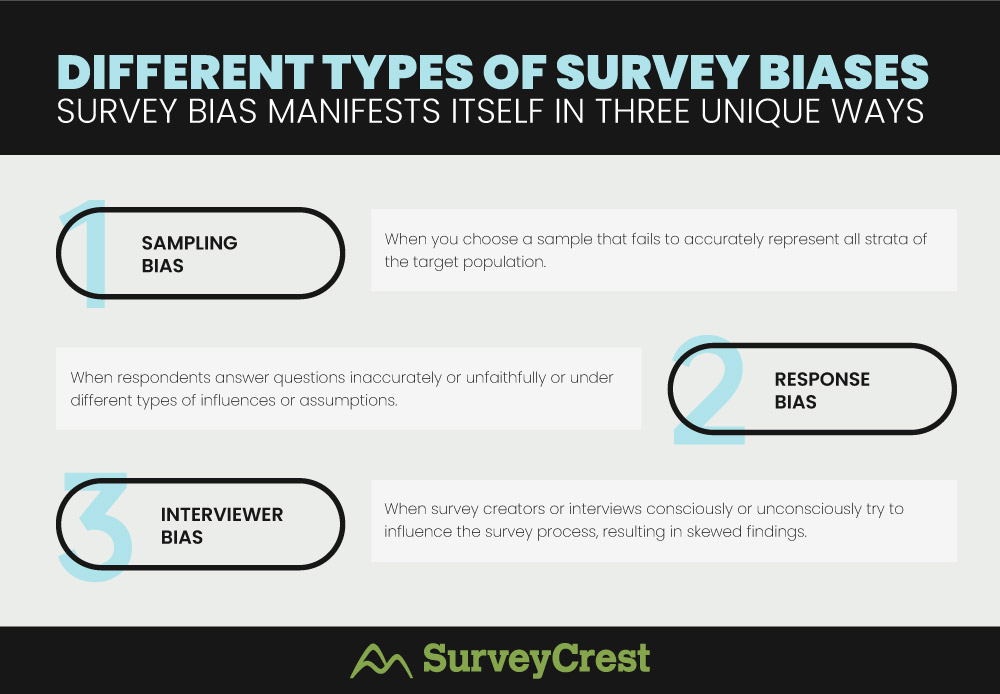

Survey bias manifests itself in three unique ways:

In today’s article, we’ll focus on Response Bias, and learn how to prevent it and minimize its impact on our surveys and research.

Response bias is any inaccuracy, distortion, or error in the data that is caused due to the way respondents have answered questions. Various factors can lead to respondents answering questions inaccurately. This typically happens for two major reasons:

Response bias is quite dangerous as it has a huge potential for rendering false results. Relying on these inaccurate findings can cause you to commit resources and efforts to misguided goals and hence create huge losses.

Response bias has several types, based on different factors that cause it.

When respondents might try to align their responses to what they think are the purposes of the study or the expectations of the researcher. In other words, they’ll modify their behavior or answers to suit what they believe the researcher wants to hear.

Example: Employees start working harder when they know a productivity survey is just coming around the corner. Their hard work is not due to any real desire to be more productive but just because of the effect of being observed.

Respondents might provide answers that they believe are socially acceptable or desirable, rather than their true opinions or behaviors. This can lead to over-reporting of positive behaviors and under-reporting of negative behaviors.

Example: In a mental health survey, some respondents downplay their anxiety symptoms to present themselves in a more socially acceptable light.

It is also called yay-saying or nay-saying. Some respondents may have a tendency to agree or disagree with statements regardless of their actual opinions. This bias can occur when respondents are not fully engaged in the survey or don’t carefully consider their responses.

Example: When you conduct an employee engagement survey and most employees seem to be agreeing or disagreeing with almost everything you say. Even to a point where their statements might contradict one another.

This bias occurs when certain groups of people are less likely to respond to the survey, due to a sampling error or just the way you have designed or administered the survey. Non-response bias leads to an unrepresentative or underrepresentation data sample.

Example: If a survey is conducted primarily on mobile, it might exclude individuals who are not comfortable with technology, potentially biasing the results.

When respondents provide extreme or exaggerated answers instead of expressing a moderate opinion.

Example: In a survey with rating scales, respondents consistently choose the most extreme answers such as, Strongly Agree or Strongly Disagree, with very few answers with other options.

It refers to a tendency of respondents to consistently choose responses that are in the middle of a response scale. It usually indicates a lack of interest on the respondent’s part.

Example: In a Likert scale survey where respondents are asked to rate their agreement or disagreement on a scale of Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree, respondents frequently choose the middle option (Neither Agree nor Disagree).

When there are questions or other elements in the survey that are not relevant to certain groups of people. It happens when researchers systematically favor certain people or unfairly assume behavior patterns for a diverse set of samples.

Example: A marketing survey that wants to know what holidays people celebrate, includes this in their survey: Do you celebrate Christmas? This excludes all cultural groups from the survey who don’t celebrate Christmas but do celebrate other holidays such as Holi, Eid, or Hanukkah.

Order bias occurs when the placement or sequence of questions in a survey influences how respondents answer those questions. Participants may give more weight to earlier questions or recall the latest items more clearly. The order in which questions are presented can impact participants’ interpretations, and thus their responses.

Example: Asking about benefits before drawbacks might lead to more positive responses.

When the mobile surveys intends to ask people questions from their past that they cannot recall. Or may recall incorrectly. It often happens when you are asking about things that happened more than a year ago from the time period of the study.

Example: A study on dietary habits where participants must recall their food consumption habits over the past year. Participants might struggle to accurately remember every meal consumed, portion sizes, and specific foods eaten, leading to inaccuracies in the reported data.

As we wrap up, it is crucial to acknowledge the significance of identifying and tackling various response bias types to achieve precise research outcomes.

By being aware of acquiescence, social desirability, cultural influences, and other biases, researchers can apply proactive measures like randomized order, impartial phrasing, and inclusive participant selection. These strategies elevate the quality of data and guarantee the dependability and authenticity of research discoveries, making for more comprehensive perspectives that genuinely reflect participants’ views.

Kelvin Stiles is a tech enthusiast and works as a marketing consultant at SurveyCrest – FREE online survey software and publishing tools for academic and business use. He is also an avid blogger and a comic book fanatic.